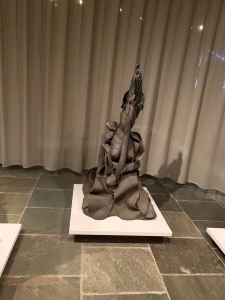

I recently had the privilege of attending a large exhibit of the sculptures of this extraordinary woman (1949-2015). Although her work is probably not to everyone’s taste, I believe you can appreciate the imagination, sheer artistry, and dexterity she demonstrated.

I regret that my photos—taken on site and from the book I purchased—do not adequately capture her genius.

In a career spanning 40 years, Mukherjee focused on creating large, elaborate fiber structures and later turned to ceramic and then bronze pieces. I found her fiber works awe-inspiring in their beauty—or deliberate ugliness—and size.

Mukherjee’s fiber was a type of rope called San or Shani, which she said was “something close to hemp…I don’t know whether it is flax, but it is not jute. Maybe it is something in between.”

She had to stop generating these fiber pieces, according to the exhibit’s program guide, because “working with fiber was physically demanding, the rope Mukherjee used was now being combined with synthetic fibers, and a ban was imposed on the dyeing units needed to achieve her preferred colors.”

Mukherjee was the daughter of artists. She spent her childhood in part in the Himalayan foothills and in West Bengal, India. Those were the areas that nurtured her love of the natural world.

She was encouraged by parents who were drawn to nature; her father developed an ecological philosophy studying at a school founded by Tagore, the poet who has also been called a polymath, or Renaissance man.

After earning a diploma in painting, she studied mural design with one of her father’s former students, who encouraged his own students to explore widely among varying styles of Indian arts and crafts, and to move beyond the traditional materials and approaches. She certainly internalized those messages.

Her signature style was the knotting visible in all the fiber structures, accomplished using not a loom, but “makeshift frames and armatures.”

In the 1970s, she drew from Indian mythology, using Sanskrit titles of divine entities, but applying them to figures that weren’t identifiable as plants or creatures.

The program guide suggests: “These now-biomorphic objects signified states of metamorphosis and transfiguration.”

Unlike most artists, she never made sketches first, and her works since the 1980s rarely hung from a wall; I felt their placement on a floor or hanging from a ceiling, drawing on the available space and light, enhanced their exceptionalism.

In freeing them from the wall, she said, she wanted to capture

“the feeling of awe [you get] when you went into the small sanctum of a temple and look up to be held by an iconic presence.”

She elaborated:

“My idea of the sacred is not rooted in any specific culture..my work is not…the iconic representation of any particular religious belief, rather it is the metamorphosed expression of varied sensory perceptions.”

The “anthropomorphic deities,” she stressed,

“have no relationship to gods and goddesses in the traditional iconographic sense, but are parallel invocations in the realm of art.”

When she moved on to ceramics, she was hindered by her inability to access kilns large enough for the work she envisioned, as well as an absence of the glazes she sought.

According to the book Mrinalini Mukherjee, edited by Shanay Jhaveri, she was told at the European Ceramic Work Centre that “You are always extending the material a little bit beyond what it should be. But that’s because you have not been trained, and nobody has taught you a way.”

Undaunted by the criticism, Mukherjee viewed her lack of specific training and her possible overreaching as advantages.

Jhaveri observed:

“It was through the sheer force of will that Mukherjee, by her own hand and the simple, direct manipulation of a series of materials, managed to invoke ‘awe.’”

In the early years of this century, she began working with bronze, apparently inspired by her mother’s small bronze figures. She sculpted in the lost-wax process: a mold is made of wax, into which molten metal is poured. The wax model is then melted away.

This technique, once again so different from the fiber she’d been accustomed to, required some adaptation.

One intriguing story is that she finished her cast bronze works using tools she’d obtained from the laboratory of a neighborhood orthodontist.

I can imagine her teacher’s delight if he’d learned how well she adapted his guidance to use unusual methods and approaches.

Her work has been praised for its “bewitching otherness.” Some of it was actually

“nature cast in art…the leaves and stalks she chanced upon and found arresting for their shapes were moulded in wax or plaster.”

I could go on and on about her works, but it seems best at this point to show you a sampling.

After spending several hours wandering among these highly diverse pieces, I emphatically agreed with the program guide’s conclusion:

“Mukherjee’s sculptures challenge the imagination to go beyond logic and reason and enter into a world that is teeming and full of potential.”

What are your impressions of Mukherjee’s work?

Annie

Update: In response to a query, I came across a terrific review of the exhibit, with additional photos, from The New York Times. For some reason, the article won’t hyperlink, but you can Google “Sculpture, Both Botanical and Bestial, Awe at the Met Breuer, July 11, 2019.” Here’s the reviewer’s conclusion:

“But my immediate question after seeing the Breuer show was simply: when did this artist ever rest? The sheer amount of energy generated by her formal inventiveness, self-developed virtuosity, pre-postmodern thinking, and un-Modern emotion makes for one of the most arresting museum experiences of the season. It is an astonishment.”

Some very interesting pieces. The imagination of the artists always amazes me, being more of a left brainer myself. I like all kinds of art (well, not true, some modern art escapes me). Two questions. Where is this ? How large are the pieces?

LikeLiked by 1 person

And it’s a nice change from the political angst, isn’t it? The exhibit was at the Met Breuer in New York City. That’s the former Whitney Museum that the Met has taken over. Unfortunately, the exhibit closed at the end of July. I’m not sure how large the sculptures are, but they were nearly ceiling high, so I’m guessing many were 10-12 feet. In looking for an answer to this question, I came across a terrific review of the exhibit, which I’ve noted in an update.

LikeLike

Loved this Annie. Thanks for introducing me to this artist

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re so welcome, Susie. Very glad you loved her work too. I found it amazing.

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading this. I was unaware of Mukherjee’s work. It is unusual and definitely thought provoking. Hopefully I will have an opportunity to see her work on exhibit somewhere.

LikeLiked by 1 person

According to Wikipedia, she is represented in New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks for introducing me to her

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are most welcome, Karen. Thanks for your comment.

LikeLike

I didn’t know this artist, but I like these pictures of her work. Thanks, Annie!

George

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure, George. I thought she was so fascinating that I wanted to share what I’d seen. I’m glad you like her work.

LikeLike

It’s different. I’m more of a painting type person because of my mother’s exhibits, but new to different types of art forms. Our regional gallery has a lot of installation type exhibits, which I find interesting too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It certainly is different! From the few pieces I’ve seen, your mother’s work is lovely. Is she still painting?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, but not as much this fall. She’s busy watching CNN and all the impeachment stuff! She’s having a big exhibit next fall/winter for 3 months, but it’s in a government funded gallery/museum so that means less work for me. I just wrote the submission/application and titled and selected/curated the exhibit. They will do all the hanging and tags and placards and PR etc I just have to get it there. We like those places the best as there is no pressure to sell or commission, as many of her better paintings aren’t for sale as they are her memories. It’s pretty amazing considering the bulk of her 300 or so paintings were done the last five years, after she quit driving, plus her lack of technical training. The art world is really a different place for me, as I had very little exposure to it before. There are so many good artists around, it’s very competitive.

LikeLike

Fascinating! More power to her…and to you!

LikeLike

I’m very interested in the period of prehistory—roughly 200,000 years ago. We know that people then were just like us, albeit with less technology. Those ancestors of ours were creative, and, like us, they expressed that creativity in problem solving (technology) and aesthetics. Naturally, their art used the materials they had, and the meaning and content of that art was embedded in their culture.

When I look at Mukherjee’s creations, they remind me of this fact; human art has always been embedded in its technology and culture. We know Mukherjee was influenced by Indian traditions and by the natural world, but what produced her “otherness”? What led her to the materials she selected and the forms she developed, which are so different from anything that anyone else was doing or appears to have done?

It’s intriguing to consider the origins and influences that lead to such distinctive work.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Hi, Allan—I find these concepts fascinating. “Human Art has always been embedded in its technology and culture.” Put in those terms, it seems self-evident, but to me it opens up new paths for considering aesthetics generally—and Mukherjee’s work specifically. I feel that you’ve helped me understand why I found her pieces so compelling. So thanks very much for providing the long view that links our ancestors’ expressiveness with the intellectual/intuitive efforts of a gifted contemporary artist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful artist Annie! I never heard of Mukherjee’s work. I like the Jamuni (2000) and the Vanshri (1994) If some of her work is in the New York Museum of Modern Art, Id like to see it since Im close to New York.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you think so. I was blown away by the exhibit. There’s only one piece at MOMA now, I think. You can see a photo by Googling Mukherjee MOMA. Enjoy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I am VERY late to this conversation but I just have to say how much I love these pieces. Wow. There is so much to consider here, but one thing for sure is that notion of being true to her inner guidance as well as the constant honing of her craft. Compelling. The line here that especially jumped out at me is: “Undaunted by the criticism, Mukherjee viewed her lack of specific training and her possible overreaching as advantages.” I’ve typed this out and put it on my computer, as I, too, have no specific training and am constantly overreaching. I’d love to think that’s a legitimate way to pursue one’s art. Thank you, Annie, for introducing me to the artist and her process.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, as to your lack of training, I know that’s not so. And re: constantly overreaching, I like what Robert Browning wrote: “Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?”

So glad you were as captivated by Mukherjee as I was!

LikeLike

I am not a fan of much that is considered to be modern art because much of it lacks beauty. These pieces, however, do not. I was not familiar with the artist, so thanks for this look into her pieces. The fiber works are fascinating to look upon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yet another on the growing list of items about which we agree! I don’t even know if Mukherjee is considered “modern” art; she’s created her own genre, I think.

I appreciate your making your way through my posts. If you want to skip the next one, a political take, I won’t be offended; I’m fairly sure it will annoy you. But the two after that, preceding today’s little unanticipated rant, I think you’ll appreciate—as we both place a premium on kindness.

LikeLiked by 1 person